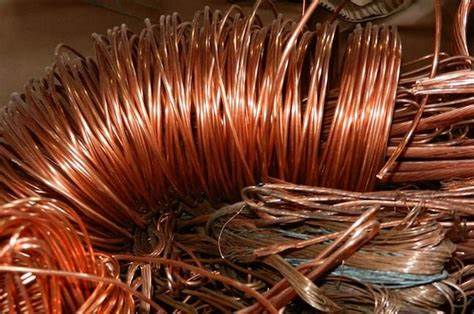

Copper prices this week fell to the lowest since last November on weak economic data from China. Yet the International Copper Study Group, a group of copper exporters and importers, just said it expected a deficit of the metal this year.

Others, such as commodity giant Trafigura, are sounding the alarm for long-term shortages, too, expecting record prices for the metal, without which the energy transition would be impossible. Yet prices remain weak. And this is a big problem.

Wind and solar installations require between eight and 12 times more copper than coal and gas generation capacity, according to the International Bar Association. EVs notoriously require three to four times more of the basic metal than internal combustion engine vehicles.

A transition to net zero would thus require much more copper than we are producing now on a global scale. According to S&P Global, demand for copper will double by 2035. According to McKinsey, by 2031, the world will face a gap of more than 6 million tons annually between the demand for copper and its supply.

The ICSG said earlier this year that only two new copper mines were brought online between 2017 and 2021. It also said that copper output last year increased by a lot less than it expected, and the same is true for this year. Something is not quite right with copper. And copper is just one of the dozen or more metals of which we would need more if we are going to hit net-zero targets.

These begin to seem extremely elusive in the context of the latest trends in the mining industry. One of these—perhaps the most worrying—is that it would now take 23 years for a mine to go from the discovery of copper to the start of actual industrial production.

That’s more than the time the UK and California have set themselves to become all-electrified in the passenger transport department. And it means there will not be enough copper for all the EVs they eye by 2035.

Just months ago, miners were talking about a decade from discovery to production, but with more stringent environmental regulations in mineral-rich developed countries and fast-evolving regulation in developing countries, this is where the industry is at: 23 years, according to data from consultancy Airguide, as reported by Reuters’ Clyde Russell.

The numbers, interestingly, were reported at a mining industry conference where attendants failed to find anything nice to say about permitting regimes in most mineral-rich jurisdictions, too.

The U.S. administration has been promising faster mine permitting, but even if it lives up to that promise, there are activists to consider, too—activists who might like wind and solar, but seem to like nature as it is more. And who have proved they can stop new mining developments.

What’s more, activism of this sort is evolving, and now commentators have coined a new term to replace the widespread not-in-my-back-yard sentiment among both activists and regular taxpayers. Instead of NIMBY, they are now talking about BANANA, or Build Absolutely Nothing Anywhere Near Anybody.

These people, Russell says in his report, are, for the mining industry, the same people who are the loudest proponents of the energy transition. And they are effectively the people who are hard at work to make that transition impossible.

These somewhat ironic challenges come on top of more fundamental ones, such as falling ore grades and a significant drop in the number of new discoveries. The dynamics within the industry have changed, too, Russell notes in his report on the Mining Investment Asia summit.

Before, junior miners discovered a resource, proved it and then either raised more money to develop it or passed the baton to one of the big players. Now, junior miners are suffering a shortage of project leaders, and large miners are reluctant to invest in new discoveries. Because prices do not reflect the fundamentals of copper.

Perhaps it is only a matter of time for them to start reflecting these fundamentals rather than following economic reports coming out of China. Indeed, copper is in a special position as a bellwether metal, its price widely taken to indicate the direction any economy is taking. Weak copper prices normally reflect weaker economic growth and vice versa.

Yet the crucial role of copper in the energy transition should have added a vector in price-setting. It should have, but it hasn’t, and this is keeping copper prices low and funding harder to come by for junior miners on which that crucial future supply of copper depends.

“Governments could work to speed up approvals once they recognise the need for expanded mineral production, but history suggests government action really only happens when the point of crisis is already reached,” Reuters’ Russell wrote in his report.

Indeed, governments are not the fastest to act unless things are really bad, as we saw last year in the EU. But this time, governments are spearheading the surge in metals and minerals demand. They are genuinely talking about encouraging more mining activity.

But even they probably know what gap exists between talk and action. The BANANAs are lurking around, ready to stage a protest against any new mine that threatens a rare and endangered species. And that’s because a lot of people want an energy transition but without all the mining necessary to enable it. They want to have the cake and eat it too. Sadly, as history has proven time and again, this is outside the realm of the possible.

source:https://oilprice.com/